There is an old joke about a tourist in Ireland who asks a local for directions to Dublin. The Irishman replies: “Well sir, if I were you, I wouldn’t start from here”.

Treasurer Scott Morrison could find some insight from that joke in crafting the coming budget. The wisdom of the Irishman is: “If you want a decent budget, don’t start with the old one.”

Traditionally, each budget is a variation of the previous one. The Treasury boffins first set out the same spending and taxing as last year, then the ministers fiddle around the edges. If the government is bold, there might be a reform that noticeably changes a particular tax or spending item, spending may be tweaked up or down, and an old program might be rebadged as a new one.

But in the absence of such intervention, the spending and taxing we get this year will be the same as the spending and taxing we got last year.

Repeating such an incremental and conservative approach to budgeting is a mistake. It preserves taxing and spending that belong to history and should not continue.

What is needed, at least once every couple of decades, is to start from scratch. Throw out the old budget and formulate plans for taxing and spending that make sense without reference to history or the current approach.

Join the Liberal Democrats’ campaign to Reset the Budget here

Combine an analysis of where you want to be overall (top-down budgeting) with an analysis of specific programs and taxes (bottom-up budgeting). And accept that this process will be iterative and needs to be politically saleable.

Top-down budgeting

In formulating the coming budget, the government should come to a view on its appropriate size. That is, it should reject the lazy approach of simply accepting the current size of government as appropriate.

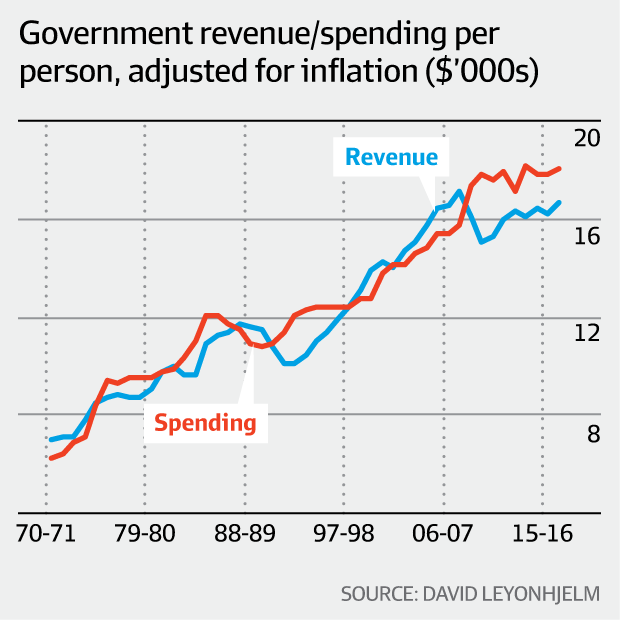

To help with this, it should look at the size of government in successful foreign countries, and in Australia during successful periods of our past.

Such top-down budgeting would be assisted by the publication of accurate figures on Australia’s size of government through history. The May budget would be the first to do this; in exchange for my vote to re-establish the Australian Building and Construction Commission, the government agreed to publish key spending and tax figures in the budget in real per capita terms. Because of this, we will be able to accurately see the size of government in the Hawke-Keating period, or in the Howard years. Anyone who yearns for a return to those governments will have a clear benchmark to aim for.

And whatever size of government Morrison deems to be appropriate, this could be legislated. So if spending ever looks like going over the limit, automatic across-the-board spending cuts would kick in.

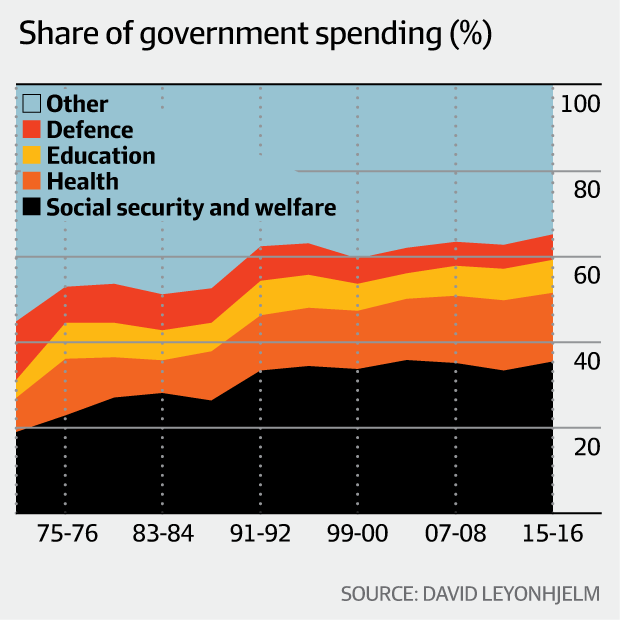

After setting its target for the size of government, the next stage of top-down budgeting would involve the government coming to a view on the appropriate share of spending among various areas such as defence and health.

Welfare spending has risen from 23 per cent of total spending at the end of the Whitlam era to 35.5 per cent now. Even if the government was comfortable with fixing the share of welfare spending at this elevated level, such a commitment would still provide budget discipline. Welfare spending is projected to rise to 37 per cent of total spending over the next two years.

Once the government comes to a view on the spending in each area, it would be up to individual ministers having responsibility in those areas to negotiate with each other as to how that spending is allocated. This is how the budget in New Zealand is created, and it works well.

After setting its target size of government, the Coalition should also come to a view on the appropriate share of revenue from various taxes. Corporate taxes have risen from 9 per cent of total tax in the mid-1980s to more than 16 per cent now, one of the highest corporate tax shares in the developed world. Even if the government was comfortable with targeting a share of corporate taxation around this level, such a commitment would counter the hysterical calls for even more tax on corporations investing in Australia.

Bottom-up budgeting

If you locked a group of people in a room and told them to come up with a range of spending programs and taxes that would best serve the nation, they would never come up with the dog’s breakfast that is our current Commonwealth government.

No group of public policy experts would come close. Neither would the editors of Green Left Weekly or Quadrant. This is because current spending and taxation, rather than serving some coherent ideological purpose, is the result of waves of new programs that have been created and augmented year after year, often without proper scrutiny or regard for duplication, or with an end date.

This is how we end up with Commonwealth government programs to fund yoga and poetry for public servants, Peruvian surfers in Peru, research into Tibetan philosophy, a Mary Poppins statue in Bowral, and a flagpole in Bathurst. It is how we fund someone to travel through the Middle East and come back to tell us that Islam is the most feminist religion in the world.

Even bigger bucks are spent on incentives for Aborigines to stay in dysfunctional communities, on welfare for the rich, on denying water for farmers and then paying for their irrigation infrastructure, on subsidising renewables and then paying compensation for high energy costs, on an education department that has no teachers teaching students and a health department with no doctors treating patients.

It’s also how we end up with 16 different tax rates on alcohol, when interest groups of all political persuasions favour a single rate. It is what leads to a cooked chicken being taxed differently from a frozen chicken. And it is what leads to the “simple” income-tax return form for individuals being 12 pages long, not including the voluminous instructions and tax return “supplements”.

Through bottom‑up budgeting, ministers and public servants would be required to design and budget for each program they believe the nation needs, starting from scratch. Current programs not identified as sufficiently worthy would be slated for retirement.

The results of bottom-up budgeting would be different under different governments. If I were in control, the result would be a government roughly half the size of the current one, as estimated by Parliamentary Budget Office costings (available at www.ldp.org.au and summarised in attached chart). But regardless of who is in power, bottom-up budgeting would lead to decisions to abolish at least some of the unjustifiable programs now soaking up taxpayer funds.

Overcoming resistance

There would inevitably be plenty of reasons the government could manufacture for not applying a bottom-up approach to the budget , and for not seeking to abolish unjustified programs.

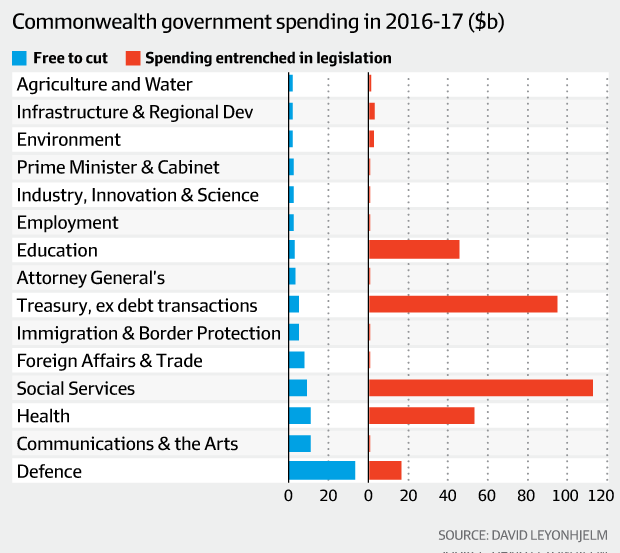

It often blames the Senate for blocking spending cuts, and it is true that $340 billion of the annual Commonwealth government spending is based on legislation passed by previous parliaments. So if cuts are to be made to that spending, Senate approval is required.

But $100 billion of the annual Commonwealth government spending is not underpinned by legislation. So cuts to this can be achieved in the budget bills, which are routinely passed by the Senate. No additional legislation needs to be passed.

As the chart indicates, the spending that can be readily cut without risking Senate hindrance — shown in blue in the chart below — is spread out across all government portfolios, with a lot of it falling under the defence, communications and arts, and foreign affairs and trade portfolios. Given the capacity to cut in these areas, the Senate is no excuse for continuing budget deficits.

The $340 billion of annual spending that is underpinned by legislation and can be cut only with explicit Senate approval — shown in red in the chart below — largely reflects state grants and welfare, health and education spending.

There are a number of reasons for optimism in winning Senate approval for cuts in these areas.

First, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull did not promise before the election that there would be “no cuts to education, no cuts to health, no change to pensions, no change to the GST and no cuts to the ABC or SBS”. That was a different prime minister, before a different election. Turnbull actually made an election commitment to live within our means.

Second, the Senate has changed. Glenn Lazarus, Ricky Muir, John Madigan and Palmer United’s Dio Wang are gone. Each of these former senators voted against spending cuts in the last parliament, such as cuts to subsidies for bachelor’s and higher degrees at public universities. Each spending cut from the last parliament should be re-tested in the new parliament, which has already shown greater fiscal responsibility than its predecessor. Cuts to subsidies to doctors under Medicare, cuts to drug subsidies under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, and an increase in the eligibility age for the age pension, should be back on the table.

A third cause for optimism is that, although Jacqui Lambie and Nick Xenophon are still in the Senate, Senator Xenophon is feeling more heat to pass spending cuts now than he felt in the last parliament. Recent media attacks on his opposition to spending cuts have stung. He hates being compared to the Greens based on his voting record. Increasingly, he will have to back up his centrist claims with support for financial responsibility. And even he has to acknowledge that, since a decade has passed since the global financial crisis and the wave of baby boomer retirements is nearly upon us, if we don’t balance the budget now, we never will.

The real resistance to responsible budgeting comes from within the government. A backbench‑driven unwillingness to make sensible spending cuts, such as including million-dollar houses in the age pension means test, is a good example. And yet, early in the parliamentary term, now is the time for the Coalition to grow a pair and deliver a budget the nation needs.

The Treasurer has a choice when it comes to drawing up the coming budget, and it would serve us all if he considered the option of not starting from where the last budget left off.