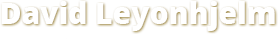

18C and the illiberal national security legislation are siblings under the skin – and both mean that we can’t be Charlie.

Note: I’ve copied and pasted the piece from the AFR here, but if you do have access, I recommend you read the piece on the newspaper’s site – it includes links to the scholarship supporting my arguments.

“I hate to break it to you, but we are not all Charlie.

The reason is simple: Charlie Hebdo was consistent in its support for freedom of speech. Its editors were not just targeted by Islamists: they’d been hauled through the French courts (where they won) and were figures of hate to both the French extreme right and conservative Catholics.

Charlie Hebdo had been out on a limb for years, true to the freewheeling anti-clericalism that owes its origins to the protests of 1968. Charb, its editor, refused to buckle.

The rest of us – with the partial exception of the United States – have buckled. There are widespread restrictions on speech, in France and elsewhere. Australia has 18C, among many others.

“Hate speech” laws are frequently based on the supposition that hate speech has the same effect as the common law offence of incitement. Incitement requires a demonstrable effect on the intended audience. Burning a cross on a black family’s front lawn, for example, amounts to incitement to commit acts of violence against that family.

It’s also important to remember hate speech laws are akin to the definition of “advocating terrorism” in the national security legislation. Because – as George Brandis told me last year – incitement is difficult to prove, governments look for other ways to restrict speech. “Advocating terrorism” in the Foreign Fighters legislation removes the requirement for demonstrable impact.

At the heart of criminalising “hate speech” is an empirical claim: that what an individual consumes in the media has a direct effect on his or her subsequent behaviour. That is, words will lead directly to deeds.

But because this is untrue – playing Grand Theft Auto and watching porn hasn’t led to an epidemic of car thefts and sexual assault – justifications for laws such as 18C and hate speech laws now turn on the notion that offence harms “dignity” and “inclusion”. Obviously, dignity and inclusion can’t be measured, while crime rates can.

Support for dignity and inclusion produces weird arguments – white people are not supposed to satirise minorities, for example. Sometimes, legislation is used – bluntly – to define what is funny.

Allowing what is “hateful” or “offensive” to be defined subjectively, as 18C does – and not according to the law’s usual objective standard (the reasonable person) – means “offence” is in the eye of the beholder. It enables people who are vexatious litigants and professional victims to complain about comments the rest of us would laugh off.

Tim Wilson, Australia’s Freedom Commissioner, has already argued18C ensures an Australian Charlie Hebdo would be litigated to death. Despite the fact 18C refers only to race, Tony Abbott’s justification for backing down on repeal was to preserve “national unity” with Australia’s Muslim community. This conflates religion with race in the crudest possible way.

This conflation is what leads to the coining of nonsense terms such as “Islamophobia”. “Homophobia” actually means something, because being homosexual is an inherent characteristic, not a choice. Islam is an idea, and it is perfectly reasonable to be afraid of an idea.

18C is far from the only potential constraint. The equivalent Victorian legislation explicitly takes in religion as well as race. A smart lawyer would bring suit in Victoria, because Charlie Hebdo would probably be caught there.

The confusion of religion for race is so pervasive – even in the US, where people ought to know better – that French people across the political spectrum have been forced to point out – while France does indeed have “hate speech” laws – they are used to protect characteristics that people cannot change, such as being black or gay.

“We do not conflate religion and race. We are the country of Voltaire and Diderot: religion is fair game” French left radical Olivier Tonneau wrote in response to repeated claims that attacking Muhammad or Islam was racist.

Apart from being unsupported by anything approaching evidence, hate speech laws have serious unintended consequences. Recently, British polling firm YouGov surveyed British attitudes to Muslims and discovered Britons see Islam negatively, but are unwilling to say so.

In other words, governments and law enforcement have to rely on anonymised polls conducted by private firms to find out what people really think.

It’s not maintainable to have partial freedom of speech. The fact that most Western countries now do makes what little freedom we still have harder to defend. Muslims who respect arguments for free speech can’t help but notice our inconsistencies. Anyone who thinks they don’t notice is guilty of treating people who profess a certain faith like children.

We won’t be Charlie until we have purged 18C, its state-based equivalents and the illiberal national security legislation from the nation’s statute books.”